New museum raises questions concerning black progress

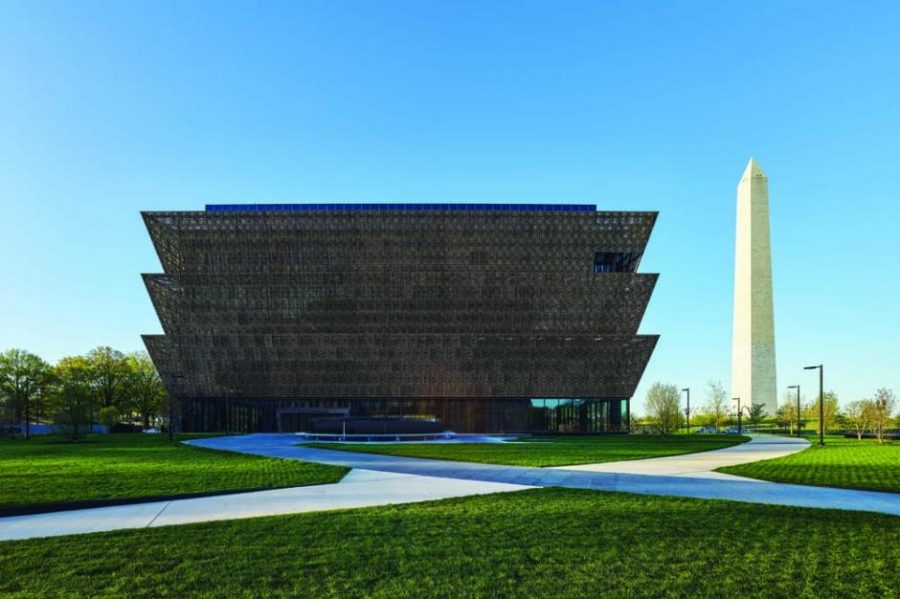

The National Museum of African-American History and Culture (NMAAHC) opened to the American public on Saturday, September 24, 2016 at the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

The idea of establishing the NMAAHC has existed since the beginning of the 20th century as an organization of African-American veterans, formerly a part of the Union Army (of the American Civil War) had originally pushed for a museum of such kind.

Efforts by many political figures and organizations much later in the century, such as Tom Mack, African-American chairman of a Tourmobile, and Representatives John Lewis (D-GA) and Mickey Leland (D-TX) have failed due to a lack of congressional approval or funding, until 2001.

Some of the original arguments and opposition against the establishment of such a museum was not only from members of the U.S. Congress. Small, privately-owned, and locally funded African-American museums and cultural centers throughout the country that had fought for the majority of those employed in their museums to be African-Americans, for financial resources for the functioning and maintenance of the museum, and for creative and academic independence from non-black, governmental control.

But for many others regardless of social and political associations and identities, the opening of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture has been a glorious educational and cultural achievement. On Saturday, September 24, 2016, approximately 12,000 visitors attended the opening of the NMAAHC in Washington, D.C. Another 19,000 visitors attended the following day. In attendance were regular citizens of all races, ethnicities, and backgrounds. Others such as sitting President Barack H. Obama, former President George W. Bush, and other high-profile political, cultural, and social figures were present during the opening ceremony and presentation of the museum.

Teresa Lewis, a social studies teacher at Naugatuck High School, says that the NMAAHC would appeal to a generation of younger students who are unresponsive to traditional teaching styles and methods, calling this a hands-on learning experience in which students can better engage.

Lewis feels that the NMAAHC offers a different, often untold perspective on American history. History can be seen as a subject of storytelling, says Lewis, and these are the stories of all Americans. There certain aspects of the African-American experience that run parallel from that of different groups as a result of centuries of exclusion and separation. But there is also much more that is similar, if not exactly the same, than one realizes about African-American culture and the rest of American society.

Lewis goes further in claiming that the most significant things to be learned from this museum are about the African-American people themselves, as individuals and as communities; the activists who have significantly helped equalize our society by fighting for civil rights for all, the inventors who have helped our society progress both economically and intellectually, and those nameless individuals whose lives and stories can tell us a lot about American society and the human experience in general.

Lewis claims that not discussing race is in itself very polarizing. This is often the case as it creates anger and resentment among those groups most negatively affected towards those who have received historical or current political and economic gains from such distinctions. The subject is avoided out of fear of accusations of racism or privilege. Lewis agrees that to improve the state of race-relations and race-related problems for all groups, the systemic and often complex causes of such conflicts and issues, such as implicit biases and prejudices, within American institutions cannot be ignored.

I am in 12th grade. I would like to study political science at the post-secondary level. I chose to study journalism because the critical thinking and...