Too many of our children are confined in adult prisons

Today in the U.S. over 250,000 juveniles are incarcerated as adults every year. This number is significantly larger than any other country in the world.

With so many of the country’s children confined inside prisons with violent adult convicts, this raises the question of how are these juveniles actually being treated within a system dominated primarily by adults and how does this affect their rehabilitation process.

However, America’s history of youth incarceration cannot be discussed without mention of the country’s racial discrimination against African-Americans and other minorities in the criminal justice system.

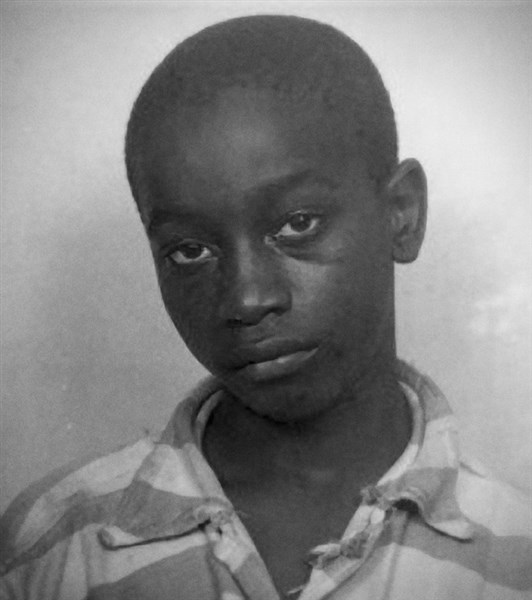

An infamous example of racial prejudice can be traced back to 1944. Fourteen years old, George Stinney Jr., an African-American boy living in South Carolina was charged for the murder of two girls, Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 8, while they were traveling along rail lines to pick wildflowers.

“They said, ‘Could you tell us where we could find some maypops?’ ” Amie Ruffner, sister of George, now 77, remembered them saying, according to WLTX-TV. “We said, ‘No,’ and they went on about their business.”

Both sister and brother freely admitted to seeing the girls before their deaths.

Because of Stinney’s race, however, he was immediately accused of the girls’ slaying despite the lack of evidence. Within the same day on April 24, George Stinney Jr. was put on trial with an all-white jury and judge that lasted only two hours. After ten-minute jury deliberation, Stinney was sentenced to death by electrocution at only fourteen years old.

It wasn’t until 70 years later after his execution that George Stinney Jr. was exonerated for the accused crimes on the basis of not receiving a fair trial because police had coerced Stinney into a confession without the presence of a parent or guardian and because there was a lack of evidence.

Even throughout modern-day this practice of coercion, although illegal, is still highly prevalent amongst minorities and juveniles. The best well-known example would be of the Exonerated Five, Yusef Salaam, Korey Wise, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, and Antron McCray.

On the night of April 19, 1989, around midnight in Central Park of New York, Trisha Meili, a 28-year-old white woman, was brutally beaten and raped and later rushed to the hospital leading to an extensive 12-day coma as she battled for her life. On that same night between 9 and 10 p.m., a group of 30-32 minors were apprehended by officials in the area for crimes of rioting.

Quickly, law enforcement connected the crimes of Trisha Meili and those involving the crowd of teens to the exonerated five boys. Once the juveniles were taken into custody, officials coerced the boys into confessions involving charges of assault, riot, rape, and attempted murder.

Police were able to receive these confessions through the use of violence and deception by making the boys believe they were only acting as witnesses.

Despite the fact that there was no substantial physical evidence each boy was convicted and received sentences between five to fifteen years.

Four of the exonerated five were sentenced to juvenile facilities while Korey Wise, the oldest at sixteen, was sentenced as an adult and served 12 years. More than half of children incarcerated in adult facilities are African-American or Latino.

Wise served the majority of his time in the notoriously violent New York City’s Rikers Island Correctional Facility.

With a child this young in a prison dominated by adults, questions arise on what truly happens behind closed doors to several other children in the same situation.

Britney Amankwah, a student in Naugatuck High School, states, “Although children are much younger than the adults they’re surrounded by, I think that they’d be treated just the same, if not worse. However, that wouldn’t be fair though because they should be treated better because of their age. It could also depend on their circumstances and the reason they got put in jail in the first place.”

In the U.S., over 4,500 children are sentenced to adult prisons. In such circumstances where juveniles are held with adults, oftentimes the minors would be forced into sight and sound separation similar to solitary confinement.

Sight and sound separation, part of the Juvenile Justice Act, requires prisons to house juveniles separate in confinement in order to protect them from physical and/or sexual violence caused by the overbearing adult population.

The separation is enacted in order “to protect kids from their own poor decisions and from adults who would harm or take advantage of them”, says the Equal Justice Initiative, to aid their chances in a healthy rehabilitation process.

Despite its good intentions for the minors, solitary confinement can be very dangerous for extended periods of time. Spending between 22-24 hours per day in physical and social isolation, inmates can suffer severe psychological damage, depression, hallucinations, cognitive defects and anxiety.

Solitary confinement can be particularly more impactful to juveniles, such as Korey Wise because unlike adults, the juvenile’s brain is still experiencing crucial brain development.

With extended periods of time confined in a room less than 80 square feet, this type of treatment can result in irreversible neurological damages. Statistically, children housed in adult prison facilities are 9 times more likely to commit suicide than those housed with other juveniles.

Once liberated from isolation into the real world, those confined in solitary are “more likely to be released without the help of a probation or parole officer,” states The Marshall Project.

Probation and parole officers are an extremely crucial component in any inmate’s rehabilitation process because their job is to mentor offenders and help prevent them from re-offending.

Although reentry into society can be a hard transition for any inmate, this process is without a doubt even more challenging for released solitary confined prisoners. They become more vulnerable to the possibility of ending up homeless, jobless or even returning back to prison without the aid of a mentor figure.

Children in particular also become more susceptible due to the fact that they have little control over their environments and oftentimes will be placed into the same situations which they had escaped from previously that led to their incarceration.

Interviewee, Britney Amankwah, 16, states, “Children returning to the real world out of solitary confinement could possibly suffer from social anxieties and illnesses because of the fact that when they were confined, the children’s brains were still developing.”

In a 2000 court case, Alonza Thomas, 16 at the time, was sentenced to 13 years in a Tehachapi, California state prison, a facility primarily made up of adults, after being charged with robbery to the second degree and assault with a firearm.

Once in prison, Thomas was separated from the adult population, however, became highly susceptible to suicide. Minors who are housed with adults become more than 30 times more likely to commit suicide than those in juvenile facilities.

“In April 2014, federal judge Lawrence Karlton ruled that the California system was subjecting mentally ill inmates to excessive punishment, blasting them with pepper spray and confining them for long periods in isolation, which, the judge said, ‘can and does cause serious psychological harm,’” states PBS.

Upon his release in 2013, Thomas now 28, suffered from severe anxiety, depression, and claustrophilia.

A registered nurse at Naugatuck High School, Kimberly Ponzillo states, “When children re-enter society from solitary confinement for long periods of time, they won’t be prepared and will have difficulty adjusting to the new, advanced world. Socialized training and job training would be needed in order for them to succeed.”

Many ex-offenders find it very difficult to find jobs, a place to stay, and lack access to several social services such as voting due to the fact that they must disclose their criminal background upfront.

Statistically, 77 percent of offenders re-offend within five years of their release. Luckily, with the support of his family today, Alonza Thomas is still striving to adapt to the outside world by writing poetry.

As more and more of our country’s children become incarcerated with others almost twice their age, increased action needs to be put in place in order to protect them within facilities and aid them in their rehabilitation process by possibly creating an alternative to adult prisons for juveniles.

Without government aid, the necessary changes, such as solitary confinement alternatives, separate facilities for violent juvenile offenders, and increased support in the rehabilitation process, not much would be done in order to improve conditions for children housed with adults in prisons.

Within the last decade, the government amended a crucial legal reform act called the Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2018 that reauthorized the original Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974 that protected the care and custody of minors.

The main objectives of the JJRA is to prevent “young people from being locked up for age-based offenses, such as truancy, running away and violating curfew, remove young people from adult facilities, with limited exceptions, keep young people who are incarcerated separate from incarcerated adults, and require states to identify and work to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system, ” states The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

As of this year, every state has participated in the act excluding Connecticut, Wyoming, and Nebraska.

I am in the 10th grade. I chose to take this class to help me with my writing. After high school I want to go into the medical field.