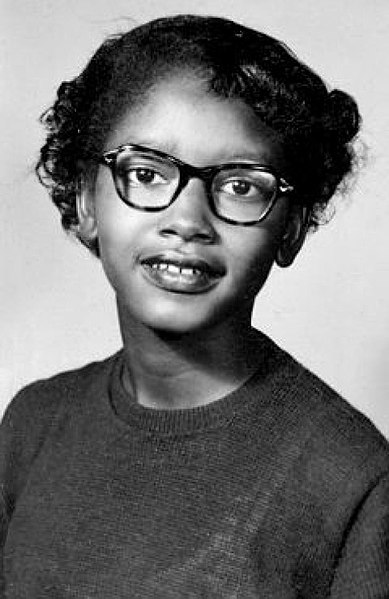

Celebrating Women: Claudette Colvin, a teenager with immense courage

On March 2, 1955, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to move to the back of the bus and give up her seat to a white person- nine months before Rosa Parks did the same thing.

According to her biographer Philip Hoose, her classmates got up and moved to the back of the bus, but Colvin did not- and the whote woman remained standing, refusing to sit in the same row as the black teenager. Under the Jim Crow laws, African-Americans did not have to yield theri seats to white passengers, however many did to avoid potentially dangerous consequences.

Colvin was well aware of what she was expected to do, but she was also thinking of the constitutional rights that had been previously discussed in school.

“I wanted the young African-American girls also on the bus to know that they had a right to be there, because they had paid their fare just like the white passengers. This is not slavery. We shouldn’t be asked to get up for the white people just because they are white. I just wanted them to know the Constitution didn’t say that.”

Two police officers boarded, yanking Colvin out of her seat and proceeded to put her in handcuffs and arrested her. Colvin says she didn’t think about how dangerous her decision was until after they made her take the stand.

“I feared they (the police) might hit me with their clubs,” she says. “They were trying to guess my bra size and teasing me about my breasts. I could have been raped.”

Colvin also remembers when the door to her jail cell closed. It was just like a Western movie, she says.

“And then I got scared, and the panic came over me, and I started crying. Then I started saying the Lord’s prayers.”

After Colvin was released from prison, there were fears that her home would be attacked. Community members acted as lookouts, and her father sat up all night with a shotgun, in case the Ku Klux Klan showed up.

Colvin was the first person to be arrested for challenging Montgomery, Alabama’s segregation policies, so her story made a few local papers- but nine months later, Rosa Parks emerged for her defiance, becoming the public figure of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).Like Colvin, Parks was commuting home and was seated in the “colored section” of the bus. When the white seats were filled, the drivers asked Parks and three other passengers to give up their seats. Parks, like Colvin, was arrested and fined.

At the time Parks was a secretary for the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP.

Although Colvin was one of the first steps in the civil rights movement, Parks rose to fame because the organization believed she had the right image to be the face of the movement. The organization didn’t want a teenager to fill the role, she says.

Another factor was that Colvin became pregnant.

“They said they didn’t want to use a pregnant teenager because it would be controversial, and the people would talk more about the pregnancy than the boycott,” Colvin says.

On the night of Parks’ arrest, there was a bus boycott demanding the desegregation in the public bus system. The boycott was effective but the city still refused to comply with the protestor’s demands- an end to the policy preventing the hiring of black bus drivers and the introduction to the first-come first-seated rule.

In Browder v. Gayle, the US Supreme Court ruled that segregation on buses must end. The legal case turned on the testimony of four plantiff’s, and one of them was Colvin.

“The NAACP had come back to me and my mother said: ‘Claudette, they must really need you, because they rejected you because you had a child out of wedlock,” she says.

“So I went and testified about the system and I was saying that the system treated us unfairly and I used some of the language that they used when we got taken off of the bus.”

After the trial Colvin continued to live in Montgomery, but struggled for years after her historical bus ride. She moved to New York at the end of the decade, and decided to stay there after teh assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Colvin remained an anonymous figure in New York, working in a Manhattan nursing home until her retirement in 2004.

Colvin’s story came out in bits and pieces; New York’s governor Mario Cuomo awarded her the MLK Jr. Medal of Freedom in 1990 and 2009, she was awarded the subject of Philip Hoose’s Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice, which won a National Book Award.

Colvin has since told reporters that she understands the politics that made Parks the face of the boycott, though she wonders why more attention hasn’t been paid to Browder v. Gayle, the landmark case that set the tone for many of the battles that followed.

With March 2 now known as Claudette Colvin Day in Montgomery, and the city unveiling granite markers to commemorate Colvin and her three co-plaintiffs in late 2019, it seems more recognition is finally coming for the overlooked hero who helped set the wheels of a new era in motion.

I am currently a senior at NHS. I love how in Journalism there are multiple ways to tell a story. Although there is a certain structure, I have more freedom...